Wow. What a day. Despite being exhausted from a week of work and nearly not finding the strength out of bed, I’m finally home from a Saturday’s conference and I’m blogging about it… so that was the impact. Huge thanks to all the speakers. I’m only sad I couldn’t see them all. However, here are 3 lessons that I took away from this year’s Warrington ResearchED.

Lesson 1: Reading Fluency

My first session was Steve Chigen who focused on how to move students from KS1 into KS2 and KS3 literacy. Assuming decoding and phonics are “in good shape”, his simple claim was this:

Complexity is both the goal and the path to the goal.

Chigen argued that the more complex texts you read, the more you are prepared to read complex texts. However, getting students to do this is not just about relying on motivational posters.

As we introduce complex texts into the curriculum, concrete strategies need to be implemented alongside these. So what solutions were given to assist early graders in literacy and reading fluency?

- Use complex texts.

Steve drew on the works of Quigley here with the quote:

“The development of reading fluence shouldn’t be seen as the job of primary schools alone. As the work of researching Tim Rasinski and others has shown, reading fluence may be more significant to older readers”.

- Coach Fluency.

This was a fascinating part of the session which backed up Haili’s ‘Using Rocket Fuel for Teacher Development’ later. Steve showed a video of a teacher coaching a young student’s reading fluency. Some of the dialogue as the following:

Example 1:

Teacher: We are going to do a fluency practise now. The goal that we are working on together is to stop at the period for just a second.

Student reads.

Teacher (after praise): Next goal is to pause as the comma. Today, I am going to give you one example, and then I want to you to keep reading inside your head and doing the same.

Teacher reads. Student then continues to read quietly.

Example 2 (a stronger pupil):

Teacher: What is your goal?

Student: My goal is when a character is speaking that I’m going to try and think about how much they might be feeling”.

I’m not sure about many primary or secondary teachers, however, I have never in my career watched professional development videos on how to assist students in their reading fluency. This 5 minute clip was hugely valuable (again, a foreshadowed plug to Haili Hughes on Session 5 which I write about later).

In summary of coaching reading fluency, Steve Chiger argued:

- Pre-select the section of the extract

- Ask students to identify their goals

- Model where necessary

- Have students read with their goal in mind

- Celebrate strong reading

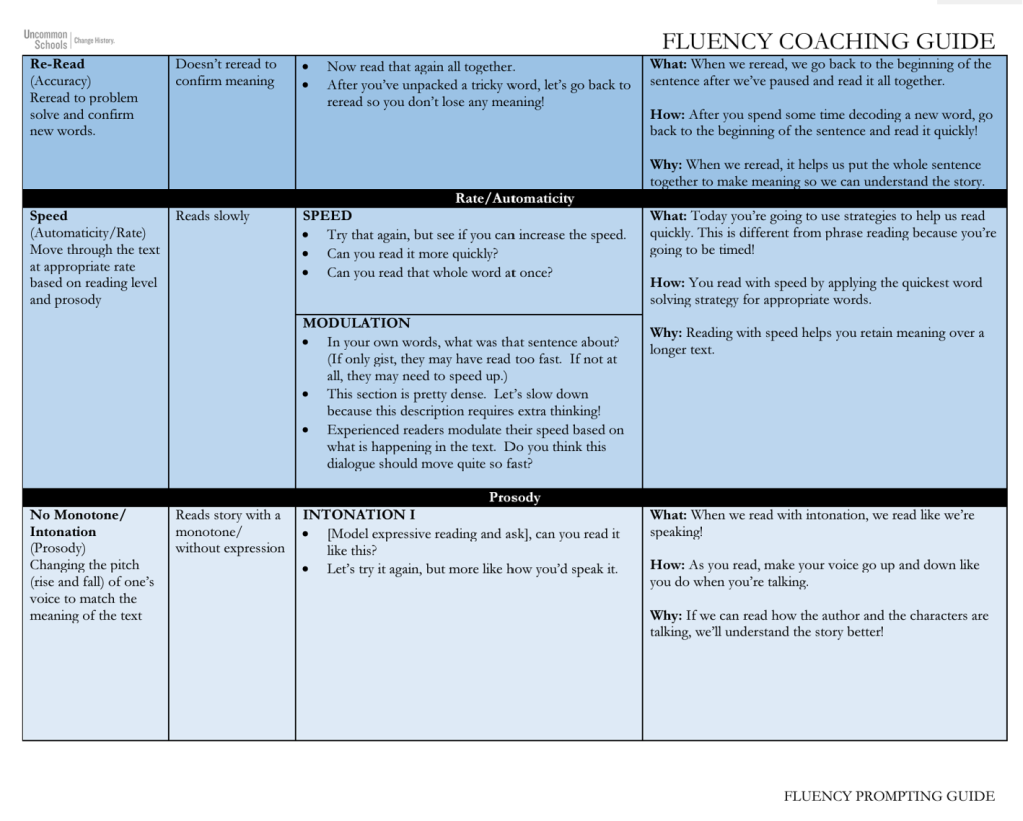

Here’s an example of one-page of his fluency coaching guide.

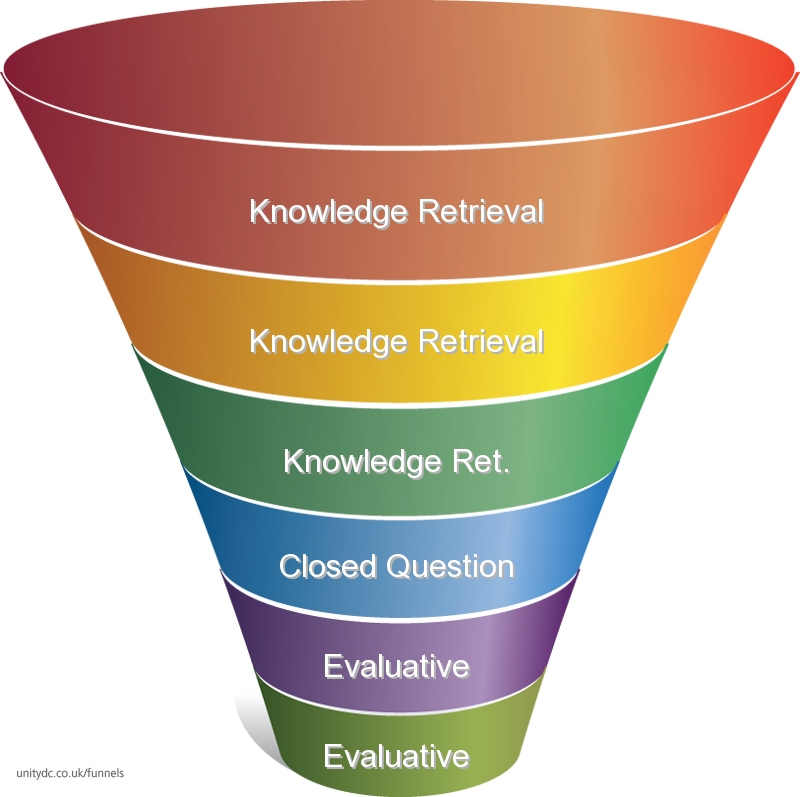

Solution 3: Activate Knowledge

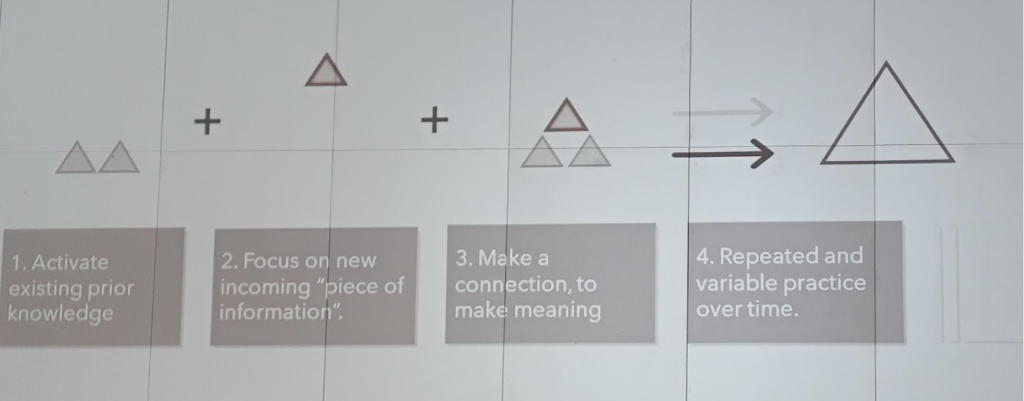

As we know by now, knowledge activates knowledge. I quite liked this simplified knowledge graphic put up by Michael Chiles in his talk on leadership as it shows the way that bringing in new knowledge – when attached to prior knowledge – can create a holistic understanding of a concept.

Chigen gives 4 clear things that will assist this:

- Integrate knowledge-building articles. i.e. Adding key vocabulary, or key information pieces to assist the contextualisation of a reading material.

- Ladder up text complexity so students build knowledge before the hardest material.

- Build units around themes or essential questions

- Map your curriculum.

You can find more on knowledge building: https://stevechiger.com/blog/

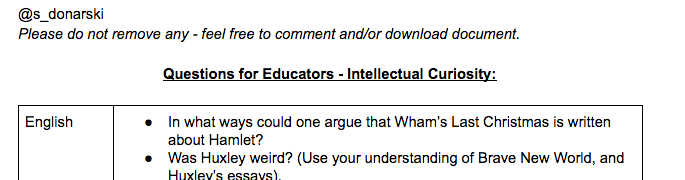

Solution 4: Making Thinking Visible

Finally, Chigen claimed that making it clear that ‘Everything’s an Argument’ assists students’ reading quality. If students can identify the text’s claims and then decide if they accept them, this assists a deep exploration of the text. He gives the following example scaffold to help find the argument – I imagine this is to be adapted depending on the appropriate year.

Lesson 2: Leadership and Strategy

This was the big one.

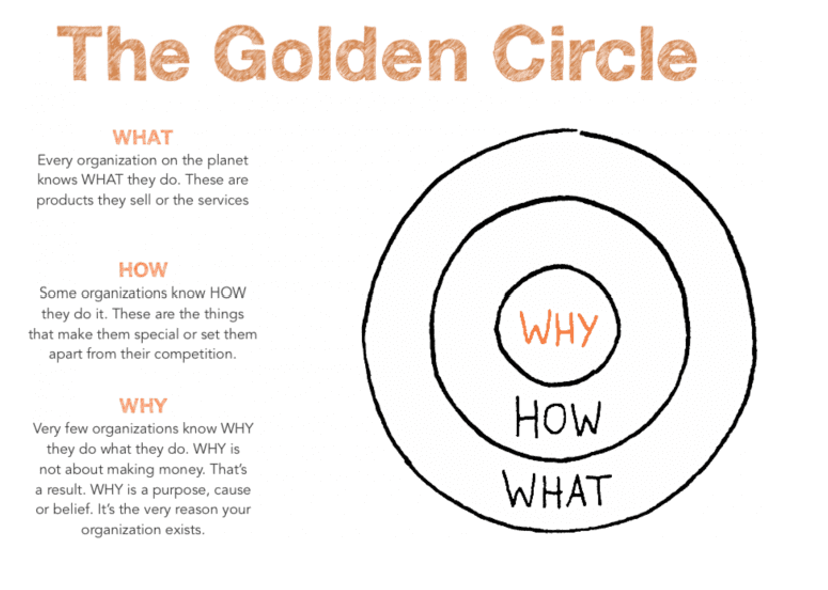

The Golden Circle

The first thing to note was that John Murphy (Great Schools Trust), Michael Chiles, and Wesley Davies, all began their leadership discussions noting the Golden Circle from Simon Sinek. That the first three questions for any leader, are these:

Murphy went one step further, adding: Lead from who you are. With a great anecdote to remind us that we are all in education with a personal story about how we got here.

Healthy teams and culture.

I use we word ‘healthy’ here to mirror a term used by Wesley Davies, but to also note Sam Crome’s comment during his presentation that ‘high performing’ is not the right word when we talk about teams as it insinuates culture of failure.

Both Sam and Wesley discussed core things that teams have. I’ve put down 9 things stated by Sam, with Wesley providing questions to help find it, as well as used examples from all presentations to flesh these out.

- Vision and purpose

- Why do we exist?

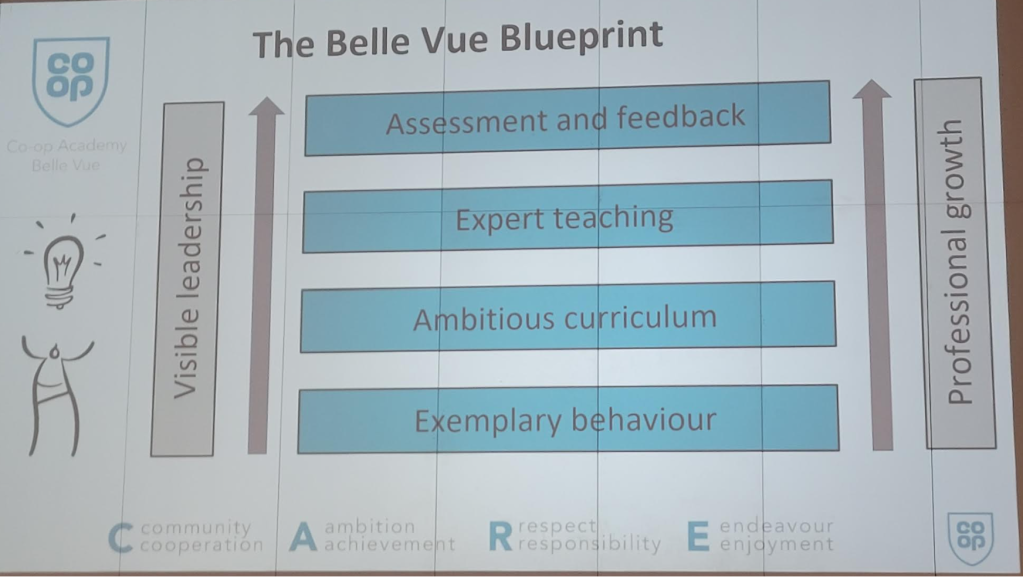

This was the first, big factor. It was clear good leaders needed a strong vision with a statement that summed up their purpose and intention. Michael Chiles shared his purpose from Belle-Vue: a knowledge rich curriculum; preparing students for their next steps; ambitious learning experience; rewards system that built intrinsic motivation. Not to mention, clear values underlying it all:

Michael said that his students are “never 60 seconds away” from seeing a reminder of these values in the corridor – constant reminders are crucial to building a collective culture.

- Belonging and Trust

- How do we behave?

For a healthy culture, this happens for both staff and students. Michael spoke a lot about this aspect for the students, drawing from Peps McCrae:

The behaviour and attitudes of others has a huge influence on our own. When a large number of people within a group adopt a similar behaviour this ‘social norm’ effect because so powerful that it can often override more formal policies and rules.

The key to doing this? Well, was to DO IT.

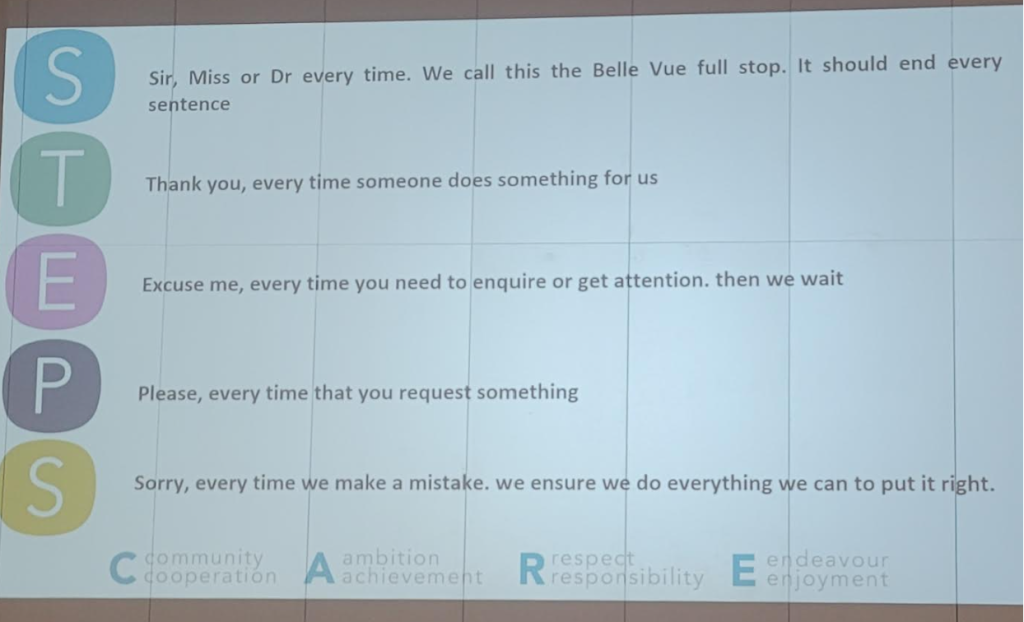

From Michael’s talk, DOING IT is about creating ‘our’ culture with the kids. Culture changes because people start doing things differently. For example, implementing their STEPS culture has meant that students now understand how to politely talk to strangers – even the likes of Tom Bennett (who recently visited Belle Vue).

For Sam, it was about ensuring that there wasn’t a lack of clarity or trust. DOING IT allows you to link to the ways you work and enables staff to “forge together” and review their work processes. All of which, hopefully creating a mechanism for constructive discussions.

- Clear and challenging goals for the team.

- How will we succeed?

For Sam, this goes back to what I mentioned above. The idea that things must be “forged together”. Sam claimed, which I completely agree with, that there’s absolutely no point getting 3 to 10 brains in a room if you’re not going to listen to all of them.

Part of Sam’s approach is that, in order for this to work, there has to be a mechanism for constructive discussion. He talked about team bonding methods to assist in developing clear and challenging goes. For example, at the beginning of term, getting your team to answer:

- What is the best version of me?

- What goes wrong?

- How might I appear when things go wrong?

By allowing your team to be open and transparent about their strengths and weaknesses, and, more importantly, what triggers them and what it looks like, the hope is that you will have a team that shares more honestly. As a result, there is knowledge development for clear and challenging goals.

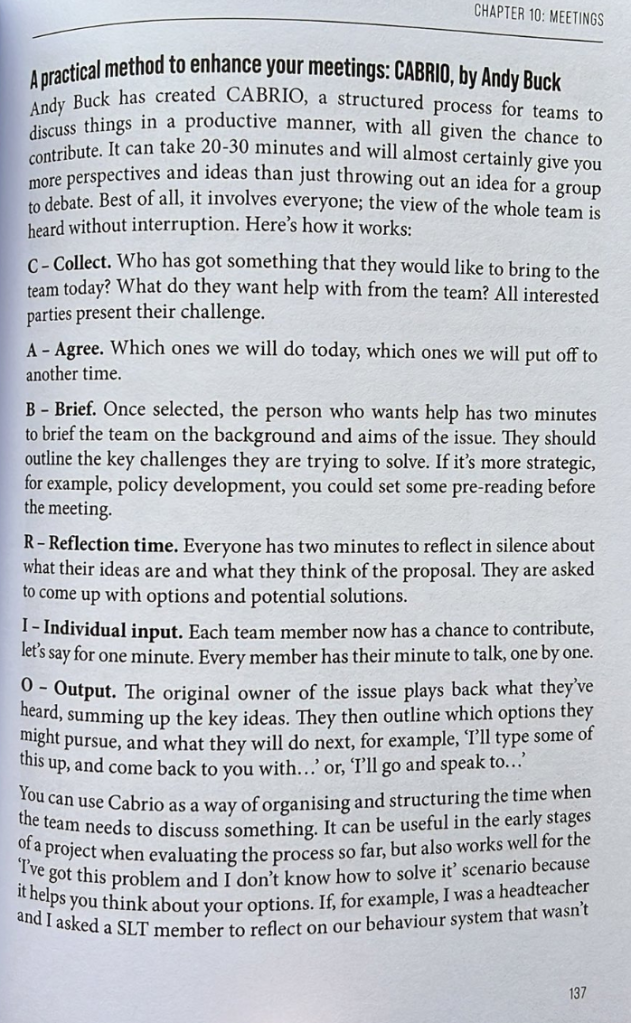

Another method discussed was Andy Buck’s CABRIO which can be found in Sam’s book: The Power of Teams, p.137.

- Role clarity, mental models, and systems.

- What do you do?

Wesley spoke really well on this using the phrase that staff must: “know their lane”. He showed a table of the areas that each staff member was clearly overseeing. For example, one staff in charge of shoes. So, if there was a query about shoes, the response is simply “you must go to Mr X as he is in charge of the shoe standards”. This was the same with blouses. By doing so, his team worked incredibly effectively.

Sam also looked at the importance of role clarity with regards to purpose and quoted from another fantastic book on Building Culture with this:

Having absolute clarity of purpose enables everyone to move in the same direction – Lekha Sharma.

Michael also looked at staff roles, however, took this down to a pupil level as well. He drew on Belle Vue’s behaviour policies claiming that, because “everything is scripted and predictable” for the students, “working memory is freed” and students know what to expect. As a result, they learn better.

Therefore, role clarity in teams (staff or pupils) not only gives people purpose, but opens up the freedom to think.

- Communication, candour, conflict

- What is important, right now?

My favourite part of this was Sam Crome stressing in his talk to beware of compliance. He claimed that functioning teams must be comfortable with conflict, and must be able to communicate to each other grievances or concerns.

He talked about the “good vibe” team. Where everyone is eating cake and happy, but then they secretly go into the next room and disagree with what was said or implemented not sharing this with their leader or line manager, the term used was ‘cordial hypocrisy’. Rightly so, Sam warned us of these teams as he claimed that it’s:

Great to be part of a good vibe but there’s a massive dysfunction in teams not having good conversations to

make themselves better.

Cordial hypocrisy can exist out of both loyalty or fear (Solomon and Flores, 2001), but either way is a barrier from good and productive communication happening.

- Regularly debrief.

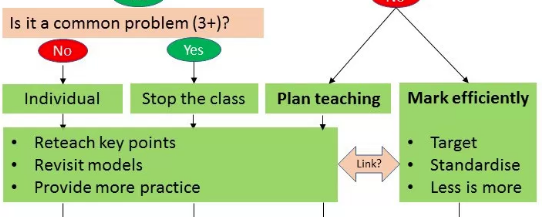

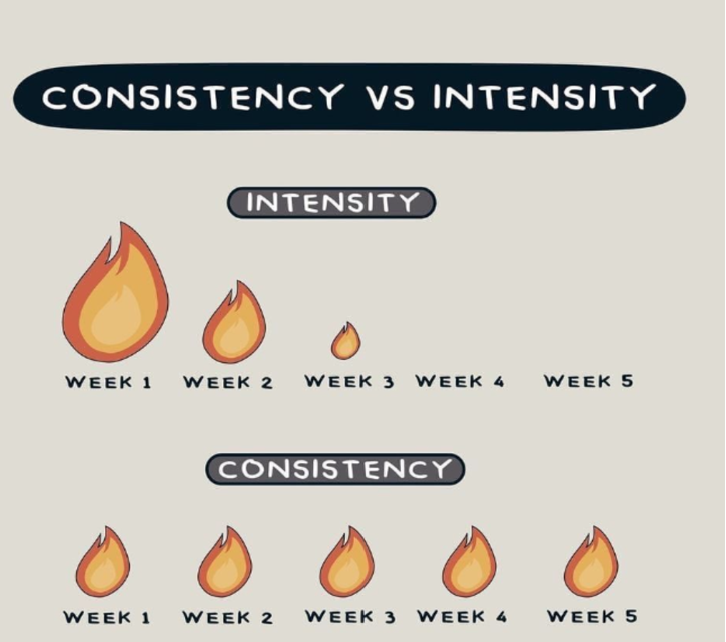

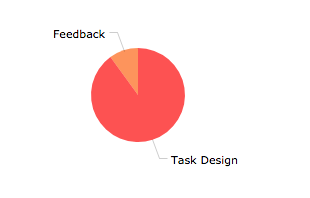

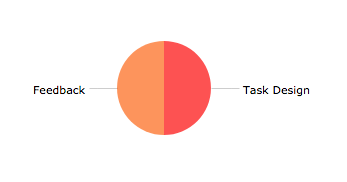

Michael Chiles argued in his talk “make a thing of the small things so the big things don’t happen” and discussed the value of intensity vs consistency with regards to the application of ideas. He put up this very applicable image:

Michael said to his audience that his organisation needed to be “consistent” as “intensity cannot be maintained”, claiming a good example are The Rules. Often schools implement ‘The Rules’ at the beginning of the year and do not regularly, on a large scale, revisit these. Michael’s talk reiterated the importance of reminding students every day what the rules were, and evaluating whether they are being met with staff.

Similarly, Wesley gave an example of SLT calling a whole-school assembly as a “reset” where necessary. This can also free up period for staff to catch up on marking or planning.

- Team diversity and characteristics

- Who must do what?

A small note here which I liked – Sam Crome recognising that good teams require a variety of personalities and thrive of each individual’s skills. Don’t surround yourself with Teams who have the same traits as this may lead to stagnation. Instead, recognise the variety of ‘work personalities’.

- Learning culture

As educators, I think this speaks for itself.

- A supportive organisation

Finally, Sam Crome discussed how to a make sure that an organisation was truly matching with the policies through effective training to promote a learning culture by being a supportive organisation.

Wesley gave two good examples of this. First, the development of policies happened with relevant staff within the organisation, and staff were given time to ensure that this happened effectively. This will be music to some of our ears as I quote Wesley here:

“To get the behaviour policy right, we brought all of our behaviour leads off timetable for 5 days”

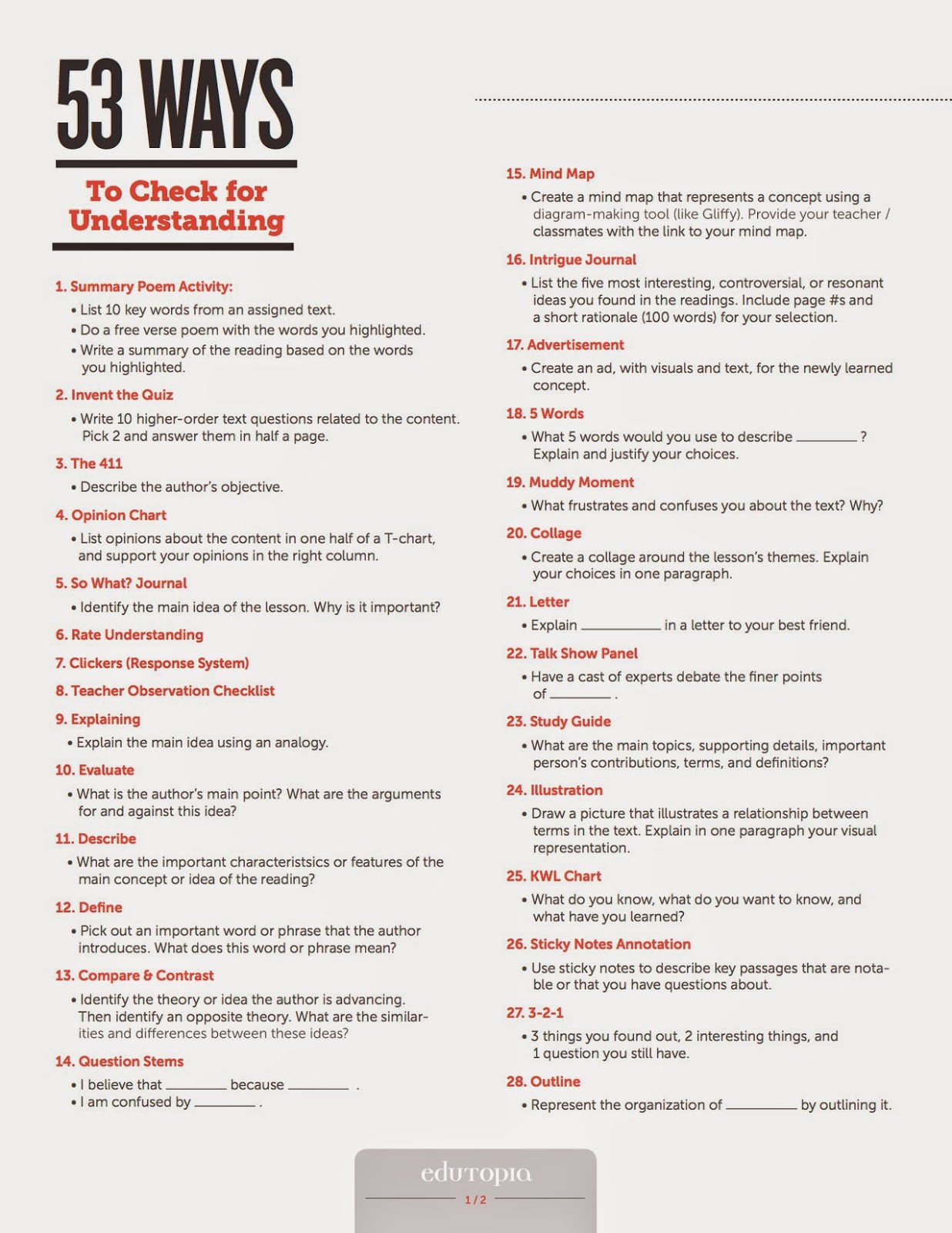

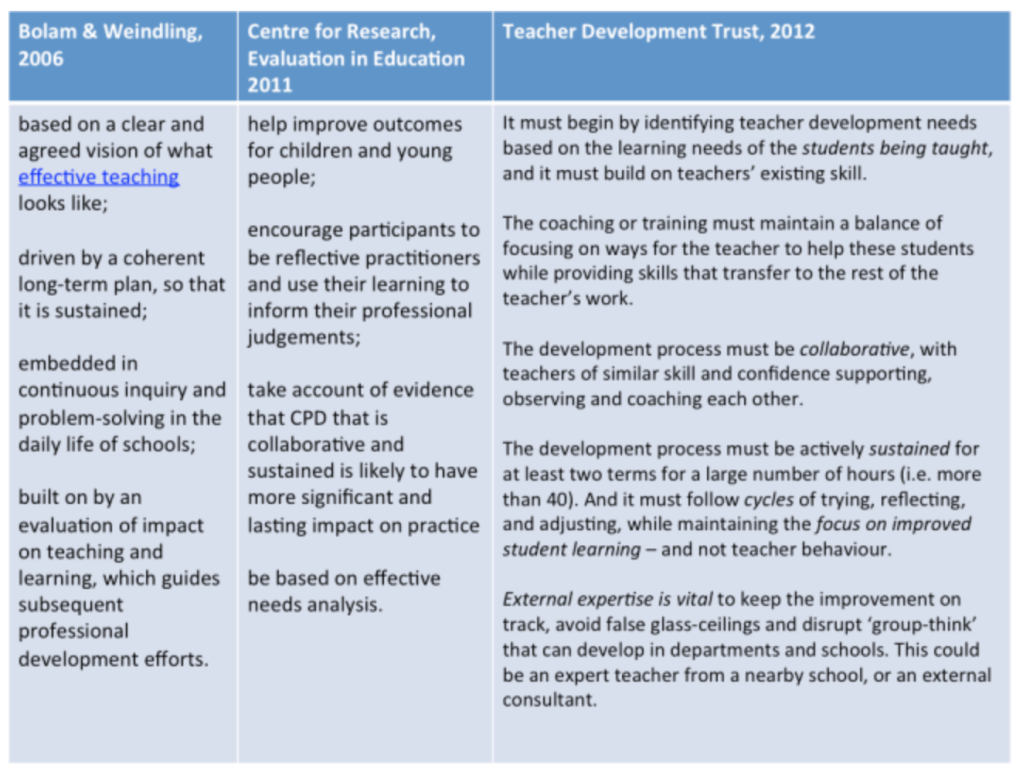

Another example is that Wesley’s trust’s CPD platform always delivers Professional Development that is linked to the learning required by new policies. There would be discussions about what sort of CPD is ‘right’ for the policy. They would offer any or all of the following (compulsory or voluntary, depending on the new learning) to their staff.

- Masterclass

- On demand

- Courses

- Events

- Seminars

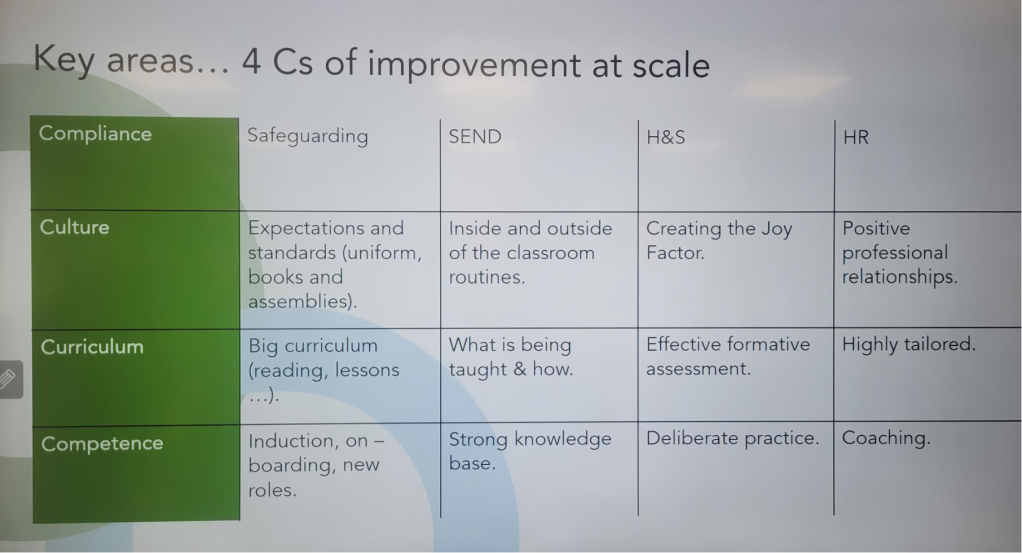

I close this area with Wesley Davies’ 4 Cs of Improvement at Scale:

My final big question to Sam at the end of his talk was this: if you’re making change within an organisation, are there always going to be staff casualties?

Sadly, it seems that this may be the case If people cannot be aligned with the vision and purpose, your organisation may not be right for them. However, what I’ve seemed to decipher as important in the process is this:

- Staff are given space to try to implement the new vision and purpose

- Staff are coached in their fears and concerns about the new vision and purpose

- Staff are mentored and given support to try

- Staff are still valued for their expertise as, whether they’re implementing a proscriptive set of rules or curricular, they’re still navigators of knowledge.

Lesson 3: Video Professional Development

Phew – we are getting there.

My final lesson of the day was from the wonderful Haili Hughes, who reminded us all on the value and power of video. Her title for the session ‘Using Video as Rocket Fuel for Teachers’ came from Jim Knight; the father of instructional coaching.

Haili spoke passionately about the poor CPD opportunities that teachers get drawing on statistics from TeacherTapp (2024) that claimed only 4 out of 10 teachers found their last INSET day ‘somewhat’ or ‘very’ useful. Indeed, a CPD sessions a few years ago asked all staff to hold hands and walk in a circle pretending to be planets in the solar system to show we ‘needed each other’. (I’m not even joking). This is compared to what I mentioned in my Lesson 1 earlier when I was watching the video given by Steve Chigen on coaching reading fluency. I’m an English teacher with a huge SEN cohort, and I have never been taught or observed methods of promoting reading fluency. For example,

Haili gets it right here – video is key.

Haili drew on 4 key areas where video boosted professional development, led by a capture from Dylan Wiliam:

“The only way to improve teacher quality across the system is to invest in the professional development of the teachers already working in schools – the love the one you’re with strategy.” – Dylan Wiliam

- A – Building Knowledge

- Managing Cog load

- Revisiting prior learning

- B – Motivating Teachers

- Setting and revisiting goals

- Presenting information from a credible source

- Providing affirmation and reinforcement after progress

- C – Developing Teaching Technique

- Instruction

- Social support

- Modelling

- Monitoring and feedback

- Rehearsal

- D – Embedded Practice

- Providing prompts and clues

- Prompting action planning

- Encouraging monitoring

- Prompting context-specific repetition.

As you can imagine, showing a 5 minute video (Haili argued this was a good amount of time) to discuss on a teaching technique, encourages teachers to ‘zoom in’ to teaching methodologies. Such practice can help new teachers not only with mimicry but genuine self-reflection. I.e. short-burst videos discourage superficial bias reflects such as “my voice is annoying” or “why was I wearing that” and allow teachers, as Haili rightly put it, to GET BETTER QUICKER.

It is so easy to see how video can match the 4 areas of professional development above.

It also made me reflect on learning about Wait Time years ago. I attended a conference with Doug Lamov on Wait Time and this video was shown – it is one I still think about. Watch the girl in the top-right corner. She is thinking and does not put her hand up, however, eventually she does. Whilst she does not get picked, if we do not implement Wait Time, we do not always give students the chance to think:

Haili’s talk was excellent as it drew from many recent research findings, and had a range of video examples from her outstanding work with IRIS Connect. Also, ending with a large-scale research project involving 1000 teachers proved that video based teacher coaching improved outcomes by +2months.

An outstanding day and the length of this blog is testament to everything that I came away with. Shout out to Kate Jones and Miriam Hussain whose sessions I could not make. Not to mention, a quick run in with Nick Pointer (https://nickpointer.com/) at the end of it who will, undoubtedly, write up his own excellent review of the things I have missed.

Thank you, ResearchED, for continuing to engage our professionals.

Firstly, Happy 2019.

Firstly, Happy 2019. ResearchED National Conference (2018) and Scotland (2018) have been the best yet. Both events contained some of the most stimulating discussions in Education. It was a triumph to see teachers of all experiences debating and challenging the ways we can better our practice – that these events occur on a Saturday and are attended by teachers across the country is a testament to our dedication to get this right.

ResearchED National Conference (2018) and Scotland (2018) have been the best yet. Both events contained some of the most stimulating discussions in Education. It was a triumph to see teachers of all experiences debating and challenging the ways we can better our practice – that these events occur on a Saturday and are attended by teachers across the country is a testament to our dedication to get this right.