In his famous commencement speech ‘This is Water’, David Foster Wallace begins with the following didactic tale:

There are these two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, “Morning, boys, how’s the water?”

And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, “What the hell is water?”

And continues to assert:

The immediate point of the fish story is that the most obvious, ubiquitous, important realities are often the ones that are the hardest to see and talk about.

It is a statement that encourages us to consider the aspects of our immediate world that we may have become ignorant of, or oblivious to. It is easy for us to slip into habits, or belief systems, without considering other options.

Yet the most significant and valuable asset to understanding ourselves, and the world around us, is being able to consider opinions and perspectives that are beyond our immediate experience. Being able to, as Wallace so eloquently puts it, ‘see the water’ as an objective and thoughtful onlooker.

As an Australian, I grew up in an entirely different Education system. The perspective of another ‘way to do things’ has simultaneously become the best and worst thing about my teaching. On one hand, I appreciate the academic rigour and standard of the UK System, on the other, there are many things I find frustrating as I have experienced a successful system that ‘does it differently.’ The Australian system, for example, does not give pupils their Target Grades (… just one example). Imagine that?

With this in mind, it was incredibly unfortunate and disheartening to see that conferences such as ResearchED – which are dedicated to presenting a variety of opinions and perspectives on Education – were being scrutinised. It is exactly these events that continually reignite my passion for the profession; I am selfishly confirmed that there are parts of the system that are broken, whilst also challenged in my own thoughts about the learning and progress of my classes. A truly invigorating experience.

So, I wanted to put forward the top 5 things that I have learned from attending such conferences and reading current educational research. All of the following have significantly impacted my outlook on the profession since I began teaching 5 years ago. It is safe to say I would have ‘coasted’ or ‘plateaued’ in the profession had I not been continually challenged by this material.

Lesson 1: A Greater Insight into How Students Retain Knowledge

When I was doing my teacher training, I never considered to investigate the ways the human mind retains knowledge, or how one’s memory pathways are strengthened. I don’t need to cite the recent changes to the GCSE that make this information so vital, as most teachers are aware that students must be able to ‘know stuff’ to pass their exams.

Our students’ knowledge of the content and the paper must be concrete. It is not enough anymore to get by with superfluous responses or underdeveloped responses – nor can they rely on Coursework. Across all disciplines, accurate and accessible knowledge of key terminologies is vital to one’s success.

Daniel T. Willingham’s book, Why Students Don’t Like School, gives some insight into the working memory, assisting to establish the ways we might transfer information to our students. The book suggests that:

‘thinking occurs when you combine information from your environment and long-term memory in new ways’

and that this process is often

‘effortful, challenging or difficult’.

Having an awareness of how the brain processes information, and the time it takes for this to be solidified into the long-term working memory, has the following classroom impacts:

- Establishes further respect for a pupil’s cognitive limits

- Forces us to reconsider when to puzzle students – or bring in new information

- Encourages us to attempt to attach new information to previous memory pathways

- Encourages a regular or more considerate approach to classroom pace and information delivery

This is not the only example. David Didau’s book, What if Everything you Knew About Education is Wrong, explores the research of Hermann Ebbinghaus’ Forgetting Curve to make us consider the expectation of classroom knowledge and how frequently we revisit knowledge previously learned.

In order to effectively learn stuff, we need to revise it regularly – so perhaps there are ways to embed this into our classroom plans, such as the following:

- Regular low stakes testing to revisit content learned

- Interleaving subjects

- Regular homework or prep on previous content

Lesson 2: Individuals May React to the Same Feedback Differently

Questioning feedback has been an interesting topic this last year and, without doing so, I am the first to admit that I would most likely be sitting here wondering why my ‘two stars and a wish’ did not develop the academic drive I sought in all my students.

As I have mentioned in my own previous blog, and presented at Telegraph Festival of Education, there is strong suggestion that our internal bias may affect how we perceive, or react to, feedback.

Whilst you can read my thoughts here, it is important to note that this has also been explored by Didau who claims that students tend to attribute their performance to the following:

- Their ability

- The performance of others

- Their intrinsic interest in the task

- How hard they tried

- Their experience from previous learning

Now, if a pupil attributes a failed result to 1, they may take emotional offence to my feedback if they have not yet developed a high level of resilience (usually seen in younger learners), however, if they attribute it to 2 their reaction to my feedback might be one of indifference or ignorance.

As a result, they will remember their ability and/or outcome very differently. This is why so many articles (Harry Fletcher-Wood’s new book, preview of chapter here, also contains further detailed information on this) have cited the importance of responding to clear, targeted feedback: it removes personal attachment to (perceived) negative comments.

Therefore, the classroom implications become the following. We:

- Consider how we deliver feedback to different pupils

- Establish more effective ways to remove emotional attachment to feedback

- Ensure that feedback is revisited and acknowledged in an effective way

- Attribute feedback to skills that can be developed so that effective academic conversations can take place in the classroom.

- Consider how clear our targets are and whether they are understood by those in our class.

Lesson 3: ‘Making Progress’ can be an Arbitrary Measure

One thing I have noticed since living in England is that the word ‘progress’ is particularly favoured in Education. We love the word and it seems to justify a lot of actions – whether right or wrong.

Daisy Christodoulou’s read Making Good Progress explores this further. She writes:

When we assess summatively, we ‘judge the extent of students’ learning of the material in a course, for the purpose of grading, certification, evaluation of progress or even for researching the effectiveness of the curriculum.’ When making these summative judgments, it is vitally important that they have some kind of shared meaning that goes beyond the curriculum.

Indeed, it is often our perspectives of a mark that provides us with a subjective judgment on progress. Consider, for example, the pupil in your class who does extremely well on (let’s do an English example) a Macbeth paper one week, but poorly the next. The judgments we could make here are three-fold: they are making ‘insufficient progress,’ ‘their knowledge on the paper in Week 2 was insufficient,’ or ‘they underperformed that day’. All of which are subjective judgments that question the validity of the result.

Christodoulou suggests that making good progress is about reliability, forcing us to consider how we implement and use assessment to truly capture the accuracy of the results. As a result, the book:

- Forces us to consider more reliable systems to assess students’ learning.

- Encourages us to consider whether we are provided with a valuable measurement of progress.

Lesson 4: Results do not have to be limited to Data

As adults, we all know that there are skills that we have developed over time; particular those we may have never thought we would. I remember being in the bottom-set English class at the beginning Year 10, and graduating 1.5 years later 1st place in Extension English at a Grammar School. If you would have asked my teachers in Year 10 to give me a target grade, I guarantee that 1st would not have been their response.

So when we have had these experiences, why do we label pupils with their grades? Lord Bew noted in his 2011 report:

The level thresholds in KS2 tests mean that one mark can make the difference between one level and the next

And, of course

These differences will be highly significant for the individual pupil.

As was mentioned by Dylan Wiliam: 32% of pupils could be given the wrong national curriculum level. While it is important to keep in mind what a student has achieved in their earlier years, it is also important to recognise that “dubious data across wide age ranges, across different schools, and across quite different cohorts means that it is almost impossible to use this data to decide whether a school [or pupil for that matter!] is any good or not. (Didau, 2015)”

Unfortunately the only absolute truth of most school data is that it places an “intolerable burden on teachers, schools and – most importantly – children.” All of this must encourage us to:

- Consider how data is used in schools

- Consider whether league tables are accurate representations

- Ensure the wellbeing of staff is not impacted/affected by data drives

- Consider how to ensure that encouragement and success of our students is not limited by data.

Lesson 5: The Educator – not just the teacher – is valuable.

Finally, and most importantly, research in Education has encouraged me to take risks in my teaching. I do not feel stifled or limited by one approach, and certainly just consider what the most effective approach would be.

The debate about progressive and traditional teaching will continue, yet there are many academic resources that place value on a variety of methods. Alex Quigley notes this in his book, The Confident Teacher, where he places an importance on developing a confident (and competent) learner.

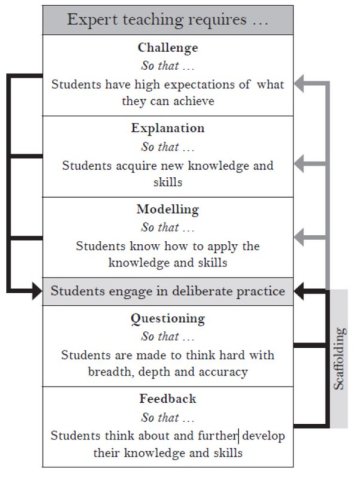

Similarly, Andy Tharby’s model (pictured above and taken from his book: Making Every English Lesson Count) on expert teaching demonstrates that educating requires explanation and modelling from a teacher (perhaps interchangeable with ‘teacher led practices’), as well as deliberate practice from pupils – a classroom method that may require teachers to step back to promote the confidence of his or her pupils. The book continues to provide a range of strategies on both spectrums of teaching to encourage and promote classroom success.

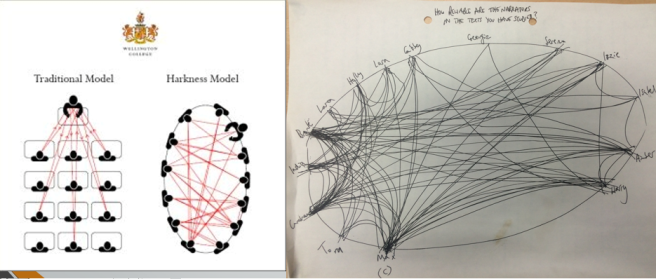

I have also written about this further as well with my interest in Harkness and Coaching methods, which can be found here, and here. However, the important implications that have come through in my readings about being the most successful practitioner are the following:

- There may be no ‘right way’ of delivering a lesson.

- Correct methods of teaching can be defined and/or limited by classroom context in that,

- Explicit teaching is effective.

- Allowing pupils space to practice may also be effective

- Encourages us to question: How can classroom planning utilise these strategies effectively?

- Forces us to consider whether we are applying appropriate methods in our own context. If not, how can we do things differently to maximise results?

In short:

We clearly have a lot to think about in this incredibly complex profession. However, I am truly grateful for all the Conferences, TeachMeets, Festivals, and individuals who (no matter what race/ethnicity/gender) enable me to see that there can be other (and better) ways to approach teaching as I begin my next academic year.

Magnificent resourceful information. I like what i’ve actually

acquired here. You make your blog posts pleasant and easy to grasp.

a

I can not wait to learn more from you. Bookmarked!

LikeLike