The Importance of Rule-Breaking in the Classroom

“Men have always shown a dim knowledge of their better potentialities by paying homage to those purest leaders who taught the simplest and most inclusive rules for an undivided mankind.” – Erik Erikson

‘Rules’ have always been something that both join and divide a society. For any society to progress into a new wave of thought, there also must be a shift in thinking – a consensus to break a rule. Therefore, we can only say that rule-breaking (or stretching) is a necessity for social progression and has been key to moving groups of individuals towards equality and freedom, and away from close-minded discrimination. It is with this thought that I preface the importance of rule-breaking in the classroom.

Over my time teaching, it has become more apparent to me how important breaking the rules are. In fact, my most exciting and ground-breaking moments as a teacher occurred when I actively took a risk to veer away from structures and used my own intuition to resolve a problem that I was faced both within the classroom and the school environment. These decisions thus led to me developing some of my strongest and greatest relationships with pupils and I believe it is necessary to share them in order to show the ways that ‘rule-breaking’ can provide the foundation for effective student-teacher relationships.

What I want to highlight in this is not necessarily the amount of rules I would have broken as a teacher but the ways they relate directly to effective social and psychological behaviour management strategies. Consequently, it becomes clear that, as teachers, we need to be subjectively thinking about the ways that behaviour management structures can limit our freedom to implement behaviour management strategies most effectively.

Rule #1: Run in the Corridors – or Verbal Contracts and Agreements

About a year ago, I was walking to my classroom and noticed a student had been sent out of his classroom for bad behaviour. Instead of ignoring him or glaring in disgust, I stopped and asked why he had been sent out. He very quickly began a monologue explaining how he had been unable to “calm down” or “relax.” His agitation continued as he discussed this with me and he would tap on the corridor post, kick his feet or fiddle with his hands. Without thinking, I decided to break the rules and I challenged him to race me to the end of the corridor and back – we had a verbal contract with the obvious outcome that the student return to class.

After sprinting past the rest of the teachers in the corridor and being beaten quite significantly by the pupil, I returned him to his lesson where he worked incredibly hard until the hour was over. This, to me, was a few seconds that I forgot about under my pile of marking by the end of the day. Two months later, I covered a class with some of the pupil’s friends to which I was surprised with: “You’re the Miss who ran down the corridor!” It meant instant admiration from a group of students I had never met before because it was clear, to this pupil, the most exciting thing that had happened to him that month.

Rule #2: March away from SLT – or ‘Mirroring’ Strategies

Another boy once, refusing to go to lesson because of troubles at home, was marching around school with SLT obviously running sheepishly behind him. Instead of attempting to stop the student – I maintained the belief that if he wasn’t going to stop for SLT, then he definitely wasn’t going to stop for me – I turned it into a game. I made him march like an army officer, as straight and stern as he could. I marched alongside with him. To the onlooker, I was sure this would have been viewed as quite a strange occurrence but in the 10 minutes we spent marching around the room, the pupil had calmed down and we marched straight back into his lesson – or, rather, I used psychological ‘mirroring’ to develop a rapport and physically show levels of empathy.

Rule #3: Eat in Class – or Implementing Effective Rewards Systems

In my teaching experience, I have been given a range pupils with varying behavioural difficulties. One of which was the (what was known as) “bottom set GCSE class.” I remember the day we were first handing the books over. My soon-to-be GCSE’s books were noticeably largely vandalised with most work incomplete, torn out or poorly looked after – so much so that the name did not have to be read to be placed into my pile.

I very quickly established routines with the group and one of which was that, provided the work throughout the week was completed with greatest amount of effort, every Thursday we would have a rewards day. This involved the following:

- Students were allowed to eat in class

- If a film or documentary was relevant, it would be possible to watch it.

And they were amazing. In fact, I grew extremely fond of all the students in this class and our Thursday rewards day became something we kept as our ‘secret.’ It was noticeably envied by other pupils which built a sense of community and pride within our class – a rewards system that was in place in order to encourage and build effective learning behaviours.

Rule #4: Graffiti the Walls – or Kinaesthetic Learning

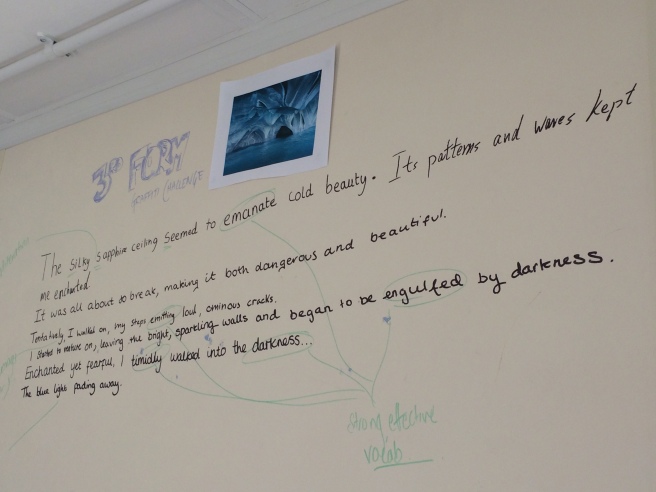

Finally, today, I challenged my students to write a brief as a ‘traveller’ to work on their creative writing skills. They were competing in teams for the ultimate classroom prize. You’re probably thinking: sweets? Chocolate? A chance to make me do a ridiculous dance? Music? Phone lessons? No. They were competing to graffiti my classroom wall with their work – a blend of kinaesthetic learning and reward giving. The winners wrote an incredible passage (as pictured below):

While the obvious flaw in this could be that, as educators, we are supposed to model behaviour and ‘breaking the rules’ isn’t necessarily Utopian role modelling. You may think: surely this establishes a paradox that encourages the students, themselves, to break the rules? I do not think so. Not only does it enable students to be confident in the idea that education is not always a restrictive prison that supresses them but it informs them that, like the world, rules can be broken provided they are done so appropriately. Also, it encourages them to see the fluidity and inconsistency of such rules and hopefully opens their mind to conceiving society beyond its current structures (which, one day, will also be outdated and archaic). Most importantly, it provided them with a personal example that teachers and school systems do listen – something that, even though we know is true, students don’t necessarily see examples of all the time.

As educators we have to show the students that it’s okay to break the rules sometimes. Surely that is how we develop our students into analytical thinkers, into evaluative thinkers and into young people who are going to make a significant difference to the problems of their world or challenge poor leadership or law. Moreover, the ‘risks’ I took in breaking these rules could always relate to social and psychological strategies that simply just veered away from the concrete behaviour management model imprinted on every classroom door.

The message: do not let your behaviour management systems take away the importance of your professional role in the classroom. Sometimes, we need to break the rules and sometimes the ‘rule-breaking’ itself is the strategy.

Hmm. I don’t disagree with the final message but I think the examples are problematic and they could, given different circumstances, have unintended consequences for other teachers in other classrooms. Effectively, it appears like you exemplify intelligent ways of developing trust with your students. I agree and I think that a good relationship – built upon trust – should be our first consideration when we think about behaviour management systems and our personal approach. Crucially, however, if that trust undermines some shared behaviour management systems deployed across the school, then we could find that you benefit, but in the classroom after, or even weeks after, students, would badger other teachers for their ‘rewards day’, and other teachers may suffer. If the school has a ‘no eating in class’ rule then students have the ammo to challenge other less fortunate teachers. We should tread carefully when we tread on our school behaviour systems.

I think you can develop the prerequisite trust and sense of pride that you describe by other means – namely, students achieving academic success.

I love ‘Dead Poets Society’ more than most, but I think it could all go a bit David Brent, and that we should be wary of romanticising rule breaking. As we are teaching teenagers we should consider that their thinking about society is yet to be fully formed. Their brain is developing and their propensity for risk and rule breaking is strong enough as it is, so we needn’t be at pains to exemplify it by example! Better, for me, to be a role model who discusses the common good of such rules, whilst promoting thinking that remains critical.

Yes – different schools have different contexts in terms of behaviour – but the psychology of behaviour is pretty universal. I like the notion of mirroring and the actions you took there, but I’d much rather your SLT deployed such conflict resolution strategies so that you didn’t have to. I’d much rather every teacher consistently considered behavioural psychology and held to consistent rules and brilliant relationships.

I am not bashing teacherly intuition and autonomy, nor do I wish to create some soulless uniformity, but on the whole I reckon we needn’t break many school rules and our students can still become great thinkers and we can still develop deeply trusting and nourishing relationships.

I may simply be representing myself as a stifling old bore here, but I think there is some criticism required to balance out your headline and core message.

Cracking blogging and please keep it up – really enjoying reading.

Alex

LikeLike

I am aware of the issues it could face, and I totally understand the concerns. I think I have been lucky, as you say, to be able to develop these relationships as well. It definitely helps and I’m always grateful to receive criticism and question. I think for me, however, the key message is to utilise professional judgement.

Interestingly, in my opinion having seen a few different schools in a variety of countries, sometimes the ‘harsher’ behaviour management systems do seem to promote a prison-like system that discourages learning overall and can build quite a negative view on education. There are definitely rules which need to be implemented; I’m certainly not detracting from that. I just believe that sometimes I think a bit of inconsistency can counterbalance the ‘consistent behaviour management approach’ that schools attempt to preach. Certainly we have cases whereby our we might use one tactic to draw a pupil back to their work and a completely different system for another. If this is true for the classroom, surely we have to consider it in the whole school approach?

I have another blog soon. Currently in editing stage. Thanks so much for the feedback, Alex.

Sarah

LikeLike

I think we are talking about continuums here from each of our perspectives.

For example, there can be a significant difference between a teacher exercising judgement, intuition and flexibility, and a teacher who breaks rules with anything like consistency.

I also think that ‘prison-like’ schools are at one pole of the continuum, but a happy medium is to be found in typical schools that deploy a consistent set of sound rules for all, which are actually more likely the norm.

I think some judicious qualifiying in your title would get nearer the truth (but would perhaps dull the intent) – ‘some minor rule-breaking’ isn’t so snappy!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much for the feedback, Alex. And I do agree – I guess what’s interesting in noting continuums is that sometimes absolutes (whether rules or statements) aren’t always the right way to assess or judge a situation. I like the idea of minor rule-breaking. Perhaps I’ll put it in parenthesis in my title.

The Importance of (minor) Rule Breaking.

What do you think?

Best,

Sarah

LikeLike

Better suits I think. I know a provocative headline gets views, but sometimes it has unintended consequences for how people read it. I would keep the headlines to pull ’em in and then give them the nuance in the article. Sorry – I sound like some ancient blogger wielding hoary advice!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Done. I’m new to this so thank you 🙂 Always good to know the small details. Looking forward to hopefully meeting you at an event sometime!

S.

LikeLike